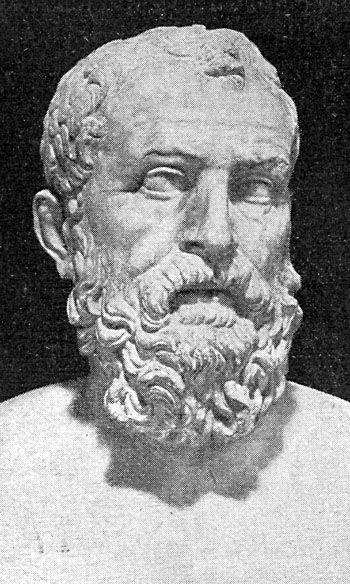

Good day, dear Take in Mind readers! Plato (428/427-348/347 BC) was the greatest ancient Greek philosopher, founder of the Academy and the Platonist tradition. His philosophical worldview is almost limitless. His works from the Corpus Platonicum presented debate and study material for many generations of philosophers, historians, sociologists, political scientists, theologians, and more. His contribution to the development of our civilization is almost impossible to evaluate. His name is deservedly on the list of the most famous intellectuals in the history of mankind… And this list of epithets can go on and on.

But today we won’t talk about Plato the philosopher, about his philosophical heritage and his contribution to modern science. No, this time we want to talk about Plato the man. And by doing that, we will also check the claim about the incompatibility of genius and villainy – this time in relation to the greatest philosopher.

What do we know about Plato? He was born in an aristocratic family during the eighty-eighth Olympic games (as mentioned in The Chronicles by Apollodorus). His father Ariston was a descendant of the last Athenian king Codras and the Athenian statesman Solon; his mother Periktion, also from a family of Solon, was a cousin of Critias, one of the thirty tyrants. Plato, the third son of Ariston and Periktion, received from his parents the name Aristocles after his grandfather.

In his youth, he prepared himself for political activity. He learned gymnastic exercises from the wrestler Ariston of Argos. Most probably, Ariston gave him the name of Plato instead of his original name because of his robust figure. But some say that he derived this name from the breadth (πλατύτης) of his eloquence, or perhaps because he was very wide (πλατὺς) across the forehead. There are some pieces of evidence that he wrestled at the Isthmian games, studied painting, wrote dithyrambics, lyric poems, and tragedies.

There is a legend that Socrates had a dream, in which he saw a cygnet on his knees, who immediately put forth feathers, and flew up high, uttering a sweet note. The next day Plato came to him, and Socrates pronounced him the bird which he had seen. The sympathy was mutual: Plato was about to compete for the prize in tragedies in the theatre of Bacchus when, after he had heard the discourse of Socrates, he burnt his poems, saying (he couldn’t resist adding some drama):

Vulcan, come here; for Plato wants your aid.

Plato decided to abandon the dream of a political career and concentrated only on philosophy. From henceforth, the twenty years old Plato became a pupil of Socrates.

After the death of Socrates in 399 BC, Plato left Athens for ten years and traveled with other young philosophers in southern Italy, Sicily, and Egypt. Once he arrived at the Syracusan tyrant Dionysius, there Plato tried to present his ideas on how to rule the state in the best way. Dionysius understood very little from Plato’s words, began to suspect the philosopher of plotting a coup, and sold the philosopher into slavery.

His friends helped him get out of this trouble by paying a ransom. After returning to Athens (approximately in 388-387), Plato bought land and established his own school, the Academy.

Many curious facts about Plato can be found in the book “The Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers” by Diogenes Laertius (3rd century AD). Here are some that may be very useful in the understanding of his personality. Nevertheless, we need to make an adjustment for the habits of the epoch and the surrounding where Plato had lived and worked.

Let’s begin:

About his relationships with other philosophers:

…He combined the principles of the schools of Heraclitus and Pythagoras and Socrates; for he used to philosophize on those things which are the subjects of sensation, according to the system of Heraclitus; on those with which intellect is conversant, according to that of Pythagoras; and on politics according to that of Socrates… And he was much assisted by Epicharmus the comic poet, a great part of whose works he transcribed, as Alcimus says in his essays addressed to Amyntas…

About Plato’s human relationships:

… Molon, who had a great dislike to Plato… Xenophon, too, does not appear to have been very friendlily disposed towards him: and accordingly they have, as if in rivalry of one another, both written books with the same title, the Banquet, the Defence of Socrates, Moral Reminiscences. Then, too, the one wrote the Cyropædia and the other a book on Politics; and Plato in his Laws says, that the Cyropædia is a mere romance, for that Cyrus was not such a person as he is described in that book. And though they both speak so much of Socrates, neither of them ever mentions the other, except that Xenophon once speaks of Plato in the third book of his Reminiscences.

It is said also, that Antisthenes, being about to recite something that he had written, invited him to be present; and that Plato having asked what he was going to recite, he said it was an essay on the impropriety of contradicting. “How then,” said Plato, “can you write on this subject?” and then he showed him that he was arguing in a circle. But Antisthenes was annoyed, and composed a dialogue against Plato, which he entitled Sathon; after which they were always enemies to one another…

…Socrates having heard Plato read the Lysis, said, “O Hercules! what a number of lies the young man has told about me.” For he had set down a great many things as sayings of Socrates which he never said.

…Plato also was a great enemy of Aristippus; accordingly, he speaks ill of him in his book on the Soul, and says that he was not with Socrates when he died, though he was in Ægina, at no great distance…

…He also had a great rivalry with Æschines, for that he had been held in great esteem by Dionysius, and afterwards came to want, and was despised by Plato, but supported by Aristippus. And Idomeneus says, that the speech which Plato attributes to Crito in the prison, when he counselled Socrates to make his escape, was really delivered by Æschines, but that Plato attributed it to Crito because of his dislike to the other…

By the way, we found another opinion (however, it is very difficult for us to judge how unbiased it is!) about Plato’s human relationships. Neoplatonist philosopher Olympiodorus the Younger (495-570) in his book “The Life of Plato” wrote:

…Here Timon the misanthrope associated with Plato alone. But Plato allured very many to philosophical discipline, preparing men and also women7 in a virile habit to be his auditors, and evincing that his philosophy deserved the greatest voluntary labour: for he avoided the Socratic irony, nor did he converse in the Forum and in workshops, nor endeavour to captivate young men by his discourses. Add too, that he did not adopt the venerable oath of the Pythagoreans, their custom of keeping their gates shut, and their ipse dixit, as he wished to conduct himself in a more political manner towards all men…

About “humanity” with slaves:

Back to Diogenes’ manuscript:

…Once, when Xenocrates came into his house, he desired him to scourge one of his slaves for him, for that he himself could not do it because he was in a passion; and that at another time he said to one of his slaves, “I should beat you if I were not in a passion.”…

Plato’s will:

…He was buried in the Academy, where he spent the greater part of his time in the practice of philosophy, from which his was called the Academic school; and his funeral was attended by all the pupils of that sect. And he made his will in the following terms:

“Plato left these things, and has bequeathed them as follows.—The farm in the district of the Hephæstiades, bounded on the north by the road from the temple of the Cephisiades, and on the south by the temple of Hercules, which is in the district of the Hephæstiades; and on the east by the estate of Archestratus the Phrearrian, and on the west by the farm of Philip the Chollidian, shall be incapable of being sold or alienated, but shall belong to my son Adimantus as far as possible. And so likewise shall my farm in the district of the Eiresides, which I bought of Callimachus, which is bounded on the north by the property of Eurymedon the Myrrhinusian, on the south by that of Demostratus of Xypeta, on the east by that of Eurymedon the Myrrhinusian, and on the west by the Cephisus;—I also leave him three minæ of silver, a silver goblet weighing a hundred and sixty-five drachms, a cup weighing forty-five drachms, a golden ring, and a golden ear-ring, weighing together four drachms and three obols. Euclides the stone-cutter owes me three minæ. I leave Diana her liberty. My slaves Tychon, Bictas, Apolloniades, and Dionysius, I bequeath to my son; and I also give him all my furniture, of which Demetrius has a catalogue. I owe no one anything”…

Let’s cite Olympiodorus again:

…When he was near his death, he appeared to himself in a dream to be changed into a swan, who, by passing from tree to tree, caused much [p. 8] labour to the fowlers. According to the Socratic Simmias, this dream signified that his meaning would be apprehended with difficulty by those who should be desirous to unfold it after his death. For interpreters resemble fowlers, in their endeavours to explain the conceptions of the ancients. But his meaning cannot be apprehended without great difficulty, because his writings, like those of Homer, are to be considered physically, ethically, theologically, and, in short, multifariously; for those two souls are said to have been generated all- harmonic: and hence the writings of both Homer and Plato demand an all-various consideration…

In general, Plato was clearly not so “simple” person. One may link this with the independence of geniuses, one with his unique charisma, and one with a multilateral view on life. Especially in this regard, I would like to end the post with the words of the greatest thinker:

The first and greatest victory is to conquer yourself; to be conquered by yourself is of all things most shameful and vile.

and

Good people do not need laws to tell them to act responsibly, while bad people will find a way around the laws.

References:

Bohn’s classical library. The Lives and Opinions Of Eminent Philosophers by Diogenes Laërtius. Literally translated by C.D.Yonge. G. Bell and sons, ltd. 1915 (reprinted by Gutenberg collection: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/57342/57342-h/57342-h.htm#page_113)

Olympiodorus’s Life of Plato. Translation by Thomas Taylor, The Works of Plato, 1804

Related Articles: